When a cancer patient survives five years from the end of treatment, most medical teams consider it a success. However, for some pediatric brain cancers, being disease-free at five years does not equal a cure.

“For a long time, we thought that surgery and radiation were pretty good treatments for ependymoma…until we realized that patients’ ependymoma tumors can recur 10 to 15 years later,” says Kathleen Dorris, MD, neuro-oncologist at Children’s Hospital Colorado and Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at the CU School of Medicine. “Once we started to realize that fact, we were more desperate to find better treatments.”

One of the major challenges in developing new treatments for ependymoma has been a lack of good ways to test new medicines. Generally, cancer scientists test new drugs against cancer cells of the type they’re trying to treat. However, many scientists found it difficult to keep cells from ependymoma tumors alive in the lab.

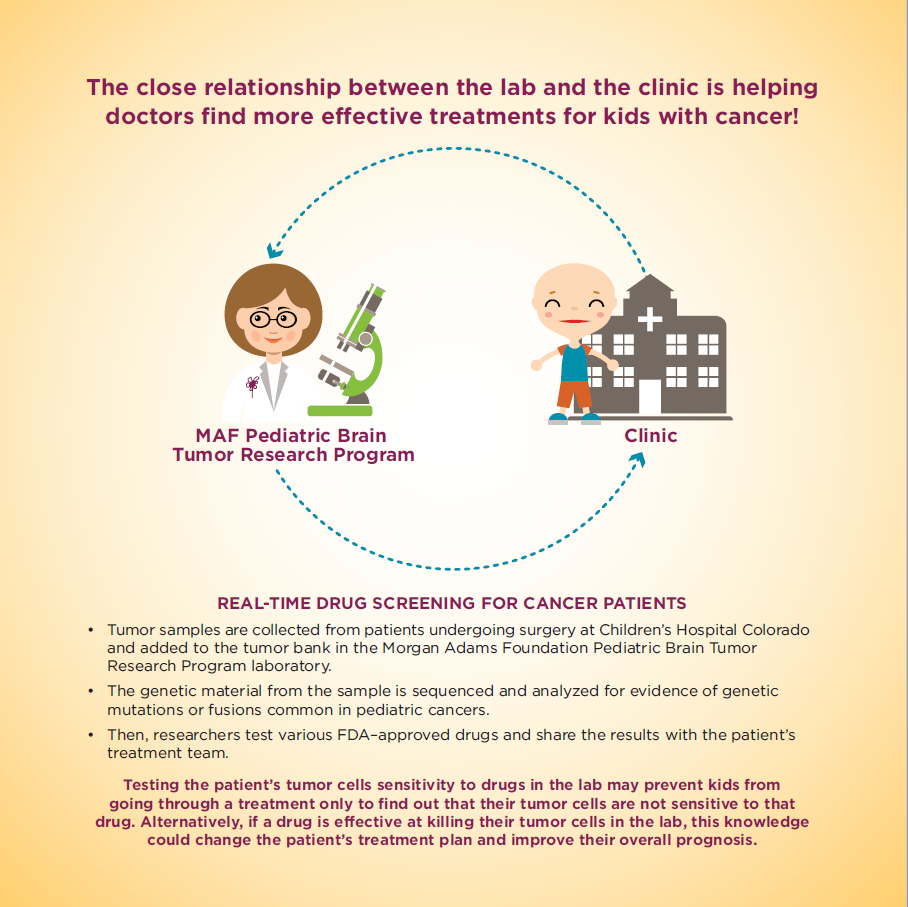

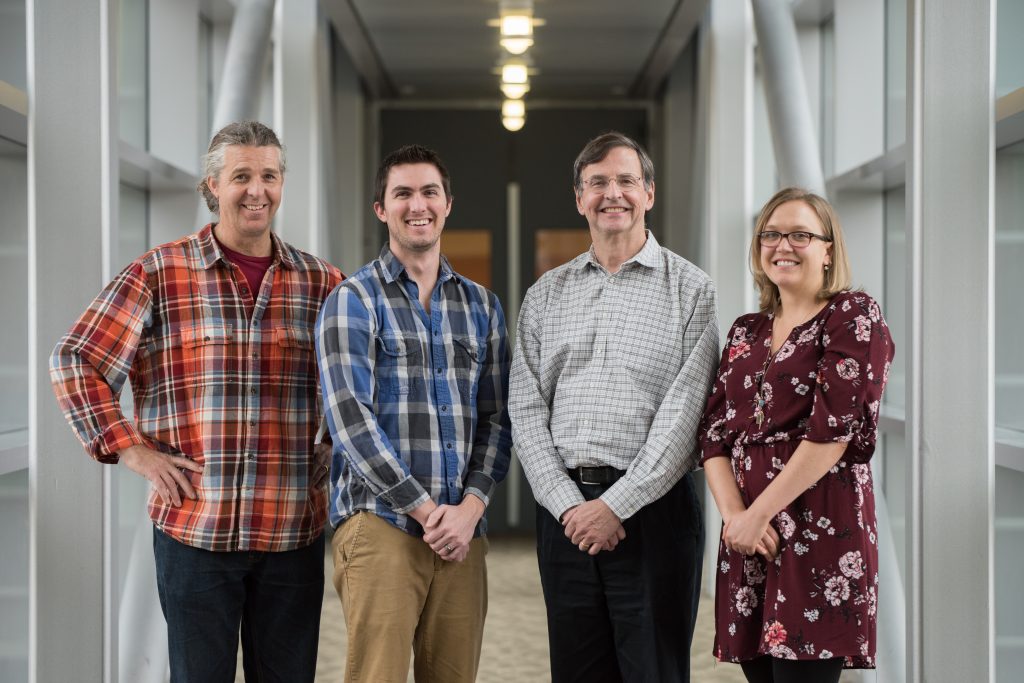

Through your support of The Morgan Adams Foundation, a team at Children’s Hospital Colorado led by Nick Foreman, MD, Seebaum/Tschetter Chair of Pediatric Neuro-Oncology, discovered what ependymoma cells needed to live outside of the patient. After successfully growing ependymoma cells from two samples donated from patient tumor tissue removed during surgery, Foreman and his team meticulously tested these cells on plates and in mouse models to ensure they performed the same way ependymoma cells do in humans. Then, with the models confirmed, the team started testing new treatments.

To do this, researchers used a technique called high-throughput screening, which (very basically) included using complicated machinery to dose ependymoma cells with over 200 known anti-cancer drugs to see which worked best. The most successful drug in the screen was a chemotherapy developed in the 1950s called fluorouracil, or 5-FU for short. Another category of medications that killed ependymoma cells was retinoids (chemicals related to vitamin A).

Dr. Dorris specializes in translating laboratory discoveries like this into new treatments and as a first step, she presented the team’s findings at scientific meetings and asked colleagues around the country for input. It turned out that a couple of other research and treatment centers around the country had already seen some success with 5-FU against ependymoma in different settings (for example to treat recurrent ependymoma). Dr. Foreman’s laboratory team was able to confirm that 5-FU works best when combined with radiation and then is followed by dual therapy with 5-FU and tretinoin (a retinoid).

Based on Dr. Foreman’s lab work, the group was able to propose a never-before-tried clinical trial for pediatric ependymoma: the addition of 5-FU to the radiation followed by treatment with 5-FU and tretinoin.

“I love the opportunity to merge patient care with research and, honestly, it’s been so rewarding to help quickly move things that Dr. Foreman is doing in the lab into a potential therapy for patients with ependymoma,” Dr. Dorris says.

The project also has the potential to attract significant new grant funding. “We’ll be applying for new funding for research tests in the proposed clinical trial to understand better the effects of this treatment approach in patients,” Dr. Dorris says. But, most importantly, this work that started with support from The Morgan Adams Foundation now results in a possible new treatment for this dangerous pediatric brain cancer.

The Foreman Lab

The Morgan Adams Foundation Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program

at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus / Children’s Hospital Colorado