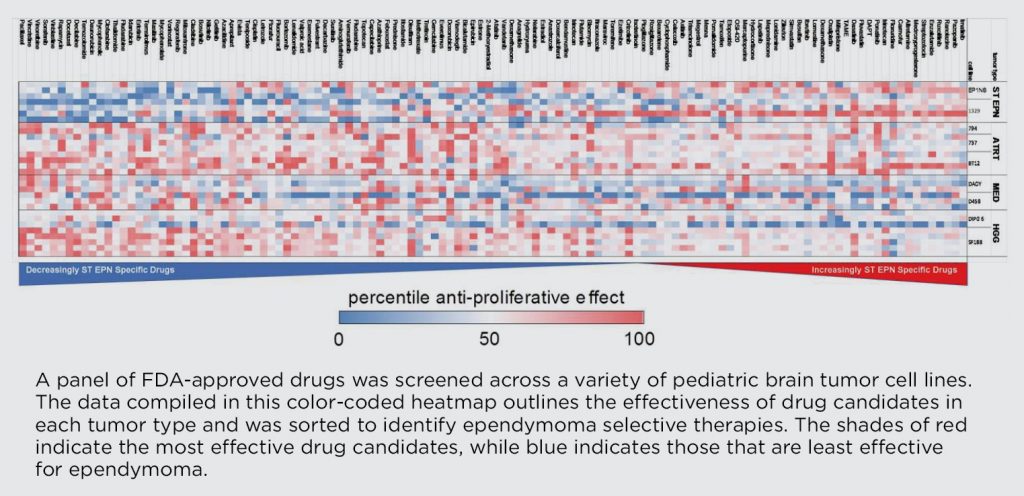

Moving groundbreaking science from the laboratory bench to the clinic so that it can have an immediate benefit to the patient is how you’re helping make progress in the fight against kids’ cancer. Members of Dr. Nick Foreman’s lab, Andrew Donson and Vladimir Amani, have systematically created drug sensitivity profiles on cell lines from major pediatric brain tumor types, including atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT), glioblastoma, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), medulloblastoma, and ependymoma. By testing drugs already approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) with known treatment effects in adults and often children, the results of this work can be rapidly applied to patient treatment plans and have an immediate effect on quality of life and outcomes in kids with brain cancer.

Researchers started by testing the drugs in established cell lines for the major pediatric brain tumor types listed above, then compared the functional results of the screen to genomic and RNA data to determine whether the predicted targets of the drugs play a role in tumor growth or not. The advent of RNA sequencing technology has made drug screening panels of this type much easier, faster, and more cost-effective than ever before, and with that, there is hope that some drugs already approved by the FDA will prove effective against these cancers, providing a fast track to clinical use.

Fluorouracil and Tretinoin, potent chemotherapy agents used for several pediatric cancers, were identified as potential treatment for pediatric ependymoma. From this, Donson and Amani published a groundbreaking ependymoma targeted therapy paper. This prompted Dr. Katie Dorris, who conducts neuro-oncology clinical trials at Children’s Hospital Colorado, to present a pilot clinical trial for ependymoma and high grade glioma to the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium. Researchers will continue to study the combination of Fluororacil and Tretinoin in the lab, and then Dr. Dorris will submit a written proposal for the trial to the PBTC.

Funding from The Morgan Adams Foundation has allowed the project to continue with the expansion of the drug screening to all tumor types, particularly those for which

there are currently no effective treatment options beyond surgical resection and radiation. The process can now be used in short-term cultures from brain tumors of children undergoing treatment at Children’s Hospital Colorado, which allows researchers to identify effective drugs for rarer tumor types that don’t have established cell lines. The Morgan Adams Foundation Pediatric Brain Tumor Research Program is one of few research facilities that has data from several short-term cultures for a variety of tumor types.

In his work on ependymoma, Amani has been screening drugs for the two main subtypes of the tumor that arise in different parts of the brain, supratentorial

In his work on ependymoma, Amani has been screening drugs for the two main subtypes of the tumor that arise in different parts of the brain, supratentorial

(forebrain) and posterior fossa (hindbrain). He has found that many drugs proposed for ependymoma treatment that are effective in posterior fossa ependymoma tumors have no effect on supratentorial ependymoma tumors, suggesting that the two should potentially be considered separate and distinct diseases.

In addition, Donson and Amani have taught fellow researcher Andrew Morin from Dr. Jean Mulcahy-Levy’s lab how to run the drug screen panels; he has been screening ATRT cell lines for prospective drugs. Morin has found that proteasome inhibitors appear to work well, especially when compared to the drugs currently used for ATRT treatment. He has started in vivo studies of a new proteasome inhibitor called Marizomib, which may be able to successfully cross the blood-brain barrier. The outcome is forthcoming, but initial results are promising, and Morin has been contacted by the drug company that owns Marizomib to discuss clinical trials.

We are very proud of the groundbreaking projects our researchers are working on every day and their commitment to finding better and safer treatment options for kids with cancer. The application of streamlined translational research using FDA-approved drugs that can be brought into the clinic quickly for immediate patient benefit is exactly what we mean when we talk about taking research from “bench to bedside” and is just one reason you’re helping researchers make strides against pediatric cancer.